Three-minute history of telephony

2014-11-11 12:44 by Ian

This is something I wrote for some coworkers in an effort to describe why the telephone signalling system is full of what appears to be arbitrary cruft and inconsistency. I thought it might be worth poasting.

The first phones looked like this:.

Notice that there are no buttons. No dial. Just the handset and a manual crank. (Using the phone used to require doing something with both hands, or your call would drop). The signalling system was a courteous human being in a room with lots of plugs and cables. You would pick up the phone and turn the crank, and a human in another nearby building would notice, plug their handset into your circuit, and ask who it was that you wanted to talk to. The service was better than Siri, but was very expensive. Akin to a time-shared secretary for the neighbourhood whose sole job it was to sit around and wait for someone to ask to be connected somewhere. Businessmen and engineers saw the profit in automating, and after a few decades of tinkering and argument....

...phones started looking like this....

Now, any noises you heard from the phone (ringing, tones, clicks, etc) were generated by electromechanical machines at your local branch exchange (the room that used to be occupied by the human operator). Those sounds were the means of automating the muscles of the human operator plugging cables and turning cranks to "ring" a bell in the correct house.

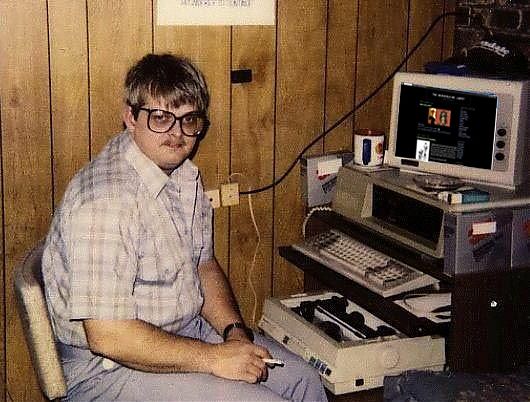

The sounds had very little meaning for humans, and if a human happened to hear the signals, it was considered as would be an unpainted water pipe or conduit; some technological infrastructure that it wasn't cost-effective to conceal. But the relays were big, loud, expensive, prone to wear out (because they were mechanical), and required guys who looked like this to maintain them constantly:

Then phones started looking like this...

...because the technology improved to the point where signalling information could be reliably generated at the customer's premises. This allowed the telephone network to scale at much lower cost because the branch exchanges didn't have to be full of cantankerous engineers and other loud machines. But there were still lots of phones being used that signalled by sparking two wires together. So the old signalling systems had to still be respected for the sake of (what we today call) backward-compatibility. The giant racks of relays and cog-work were gone, but the old spark-phones still worked because the new machines still respected the signalling standards.

Nothing changed for a long time. And the new tone-based signalling standards gained wide adoption. The internet was built on these signalling standards. Eventually, the internet got so awesome that people quit calling each other directly. Instead, they told their computers to call other computers, and convert their voices into very fast tones to be re-assembled into a voice on the other side. This imparted higher efficiency because the routing was programmable, calls could be gathered into "trunks" (rather than discrete lines), and it was impossible to charge long-distance fees (that were formerly used to pay for the long chain of human operators necessary to connect calls, and the line-space needed to maintain the call to the exclusion of other customers).

The efficiency gains were so high that engineers started building computers that were simply shaped like phones, but with signalling systems that worked NOTHING like a telephone:

When this point was reached, the telephone network was made essentially obsolete. But three generations of humans had been building and using a communication system that had evolved from making sparks on a mile-long copper wire (one step removed from the telegraph). The signalling and addressing standards are so deeply ingrained, that they are now observed for no other reason than historical inertia. Where there was once concrete purpose, there is now only symbolism. Where there once stood a building with a human operator, there is now a rack of computers that present the illusion of being 80-year-old hardware so that trained humans and other machines that don't know any better can still communicate with the rest of the world. The illusion is so complete, that you can still ring a phone in Malaysia by making well-timed sparks on your home telephone line.

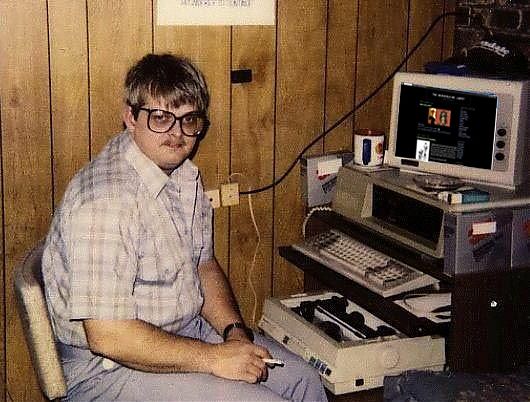

And all that is required is that it be constantly maintained by guys who look like this:

Previous: How to properly abuse a prioirty queue

Next: Removing a lodged bullet